Chapter I

A new way of looking at the world

The Three Philosophers 1

Wissensdurst

Are we witnessing a conversation about observing nature unfold here?

The oldest man on the right is pulling out a document with astronomical symbols and starting to speak.

His companion, dressed in oriental clothing, is turning toward him.

The youngest is sitting with a compass and protractor in his hands, as if he were carefully measuring something.

‘The oil painting with the three philosophers set against a landscape … with these truly wonderfully painted rocks.’

Marcantonio Michiel | Thus reads a note written in 1525 about this work of art by the Venetian painter Giorgione.

Whoever the three men are – they have dedicated themselves to research. In this way, they symbolize the growing interest in science at the turn of the early modern era. Around 1500, humanist scholars studied ancient writings in order to revise and develop them. The painting was probably commissioned by Taddeo Contarini, a wealthy and educated Venetian who read ancient manuscripts of philosophical and astronomical texts himself. The Republic of Venice was an important centre of publishing, where printed scientific texts were circulated.

Many interpretations exist for this painting.

Room for nature

Giorgione depicts the landscape in great detail. People and nature come together to form a harmonious unity. Nature itself becomes an object of research.

The trees in the background, some have leaves, some are bare. Does this hint at the change of seasons? Does nature reflect the different ages of the men?

Are the three men particular ancient philosophers and mathematicians?

Do they represent the three wise men from the Orient?

Or different religions?

Currently, there is a connection to an inscription that could be found on Giorgione's painting around 1520

‘Live by the works of the mind; death will take care of everything else.’

This verse comes from a Latin poem by Maecenas, which was widely read during the Renaissance. The motto was also found in treatises on astronomy, among other things.

Will the works of our mind – our artistic ideas and scientific insights – survive long after we are dead?

Giorgione's painting continues to leave room for many interpretations.

What time is it?

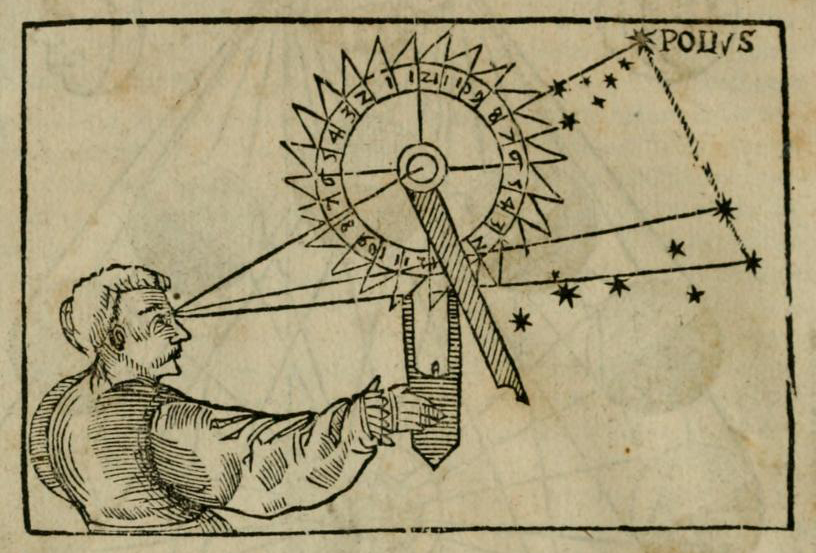

Enigmatic... The astronomical text in the hands of the oldest philosopher draws our attention. In the centre is a crescent moon and a smaller circle. Further down, a disc with jagged teeth and the numbers 1 to 7 can be seen. It represents an astronomical instrument used to determine the hours of the night based on the position of Polaris.

A woodcut from the Cosmographia by Petrus Apianus (published several times in the sixteenth century) shows such a nocturnal, also known as a horologium nocturnum or nocturlabe.

To explore the heavens, people in ancient times had already begun to design astronomical devices, which were constantly being improved upon. Many such instruments were in the possession of Emperor Rudolf II around 1600, including an astrolabe. It determined the points of the compass and the position of stars and was essential for seafaring.

1

Giorgione, The Three Philosophers, 1508/09. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Picture Gallery © KHM-Museumsverband

2

Nocturlabium, woodcut from the Cosmographia by Petrus Apianus, 1564. Getty Research Institute, public domain

Reaching for the stars

Even early civilizations used celestial phenomena to determine time. The Babylonians drew imaginary lines between the brightest points of light in the night sky to form figures or objects. The ancient Greeks and Romans borrowed their celestial figures from mythology – they also have an impact on modern astronomy.

The resulting constellations were important for orientation in time and space. Knowledge of them was helpful for dividing the year or for navigating the seas. The positions of the stars were recorded on maps.

Claudius Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy wrote an influential astronomical textbook in the middle of the second century CE, which later became known as the Almagest. The Ptolemaic system of the world, which defines the spherical Earth as the centre of the universe, determined the view of the cosmos until well into modern times.

Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi

Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi, a Persian-Islamic astronomer. In his Book of Fixed Stars, he revised and added to Ptolemy's star catalogue in the tenth century and tried to relate the Greek names of the constellations to the Arabic ones.

Marcus Manilius

Marcus Manilius, the five books of his Astronomica from the first century CE were only rediscovered in the late Middle Ages. The first printed version appeared in Nuremberg around 1473.

Aratos of Soloi

Aratus of Soli, author of the didactic poem Phaenomena in the third century BCE.

Lyre or vulture?

Dürer based his design of the constellations on older maps. He did, however, modify some figures, such as the depiction of the lyre: The ancient string instrument became a vulture or an eagle in the Arabic tradition. Dürer combined the two traditions by giving the bird a lyre body.

Map of the Northern Sky 3

A hare in the southern sky

As a master of natural observation, Dürer was particularly adept at depicting (celestial) animals with great accuracy. For example, the hare can be clearly recognized as such on the southern map.

Teamwork

Nuremberg was a centre of celestial cartography and the construction of astronomical measuring instruments.

As an artist interested in science, Dürer was in close contact with astronomers. He combined current calculations by important astronomers from Nuremberg with knowledge of ancient and Arabic traditions. Conrad Heinfogel was responsible for the position of the stars on Dürer's celestial maps. Cartographer Johannes Stabius acted as the editor. The names and coats of arms of the authors appear in the lower corner of the southern map.

The coat of arms of Cardinal Matthäus Lang von Wellenburg, to whom the maps are dedicated, is emblazoned at the top left. He was a close associate of Maximilian I.

The emperor's printing privilege is listed at the bottom right.

Map of the Southern Sky 4

Sensational!

The two woodcuts are considered to be the first printed celestial maps in Europe. They were widely reproduced and distributed.

The picture of the northern sky is densely packed with figures. The southern sky, which was even less known in Europe at the time, is considerably emptier, as the age of great discoveries had only just begun. The twelve signs of the zodiac can be seen on the arc of the northern sky. Four ancient astronomers keep watch in the corners.

Trailblazing

Dürer's celestial maps had a great influence on depictions of the sky throughout Europe. They were reflected in later printed versions as well as in three-dimensional celestial globes.

More accurate maps of the Earth and sky enabled major expeditions, which in turn increased our geographical and astronomical knowledge. Venturing into as yet unexplored areas promoted the discovery, but also the conquest of the world. The expansion of political and economic spheres of influence gathered pace.

This extended view of the world was also reflected in globes: the sphere was the ideal shape for grasping the world.

Change of perspective

Time for a change! In the first half of the sixteenth century, Nicolaus Copernicus came on the scene: he no longer placed the Earth but the Sun at the centre of the cosmos. His revolutionary idea met with resistance, particularly from the Christian church. For a long time, the Earth had been thought to be the centre of the universe, with the Sun revolving around it.

But Johannes Kepler took Copernicus's theses further: the Earth rotates on its own axis and orbits the Sun like the other planets. A far-reaching upheaval took its course, also known as the ‘Copernican revolution’.

Everything revolves around the Sun

Revolutionary new! This astronomical clock is the first to show a mechanical representation of the heliocentric planetary system. The large upper dial shows the movements of the celestial bodies: the planets known at that time – Mercury, Venus, Mars, Saturn, and Jupiter – revolve on five hands around the fixed Sun, which is located in the centre of the dial.

Jobst Bürgi, the imperial clockmaker, consulted with the court astronomer Johannes Kepler on its construction. Both worked for Rudolf II in Prague. The result: the finest craftsmanship in the service of science.

Pretty heavy

The weight of the cosmos weighs heavily on his shoulders. According to ancient myth, the Titan Atlas was condemned to hold up the sky for eternity. The hero Hercules only replaced him for a short time. In the meantime, Atlas was supposed to steal the golden apples of the Hesperides for him.

Here, Hercules is lifting a globe made of ruin marble. The artist used the natural characteristics of this special limestone: the grain pattern and different colours of the stone enabled him to recreate the continents, including their coastlines. A special kind of globe.

3

Albrecht Dürer, Map of the Northern Sky, 1515. Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München © Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München

4

Albrecht Dürer, Map of the Southern Sky, 1515. Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München © Staatliche Graphische Sammlung München

5

Johannes Reinhold the Elder and Georg Roll, Mechanical Celestial Globe, 1583/84. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Kunstkammer © KHM-Museumsverband

6

Jobst Bürgi, So-called Viennese Planetary Clock, c.1605. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Kunstkammer © KHM-Museumsverband

7

Hercules with Globe, Italy, 1st half of 17th century. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Kunstkammer © KHM-Museumsverband